— Cenocracy: On the path of a New Government —

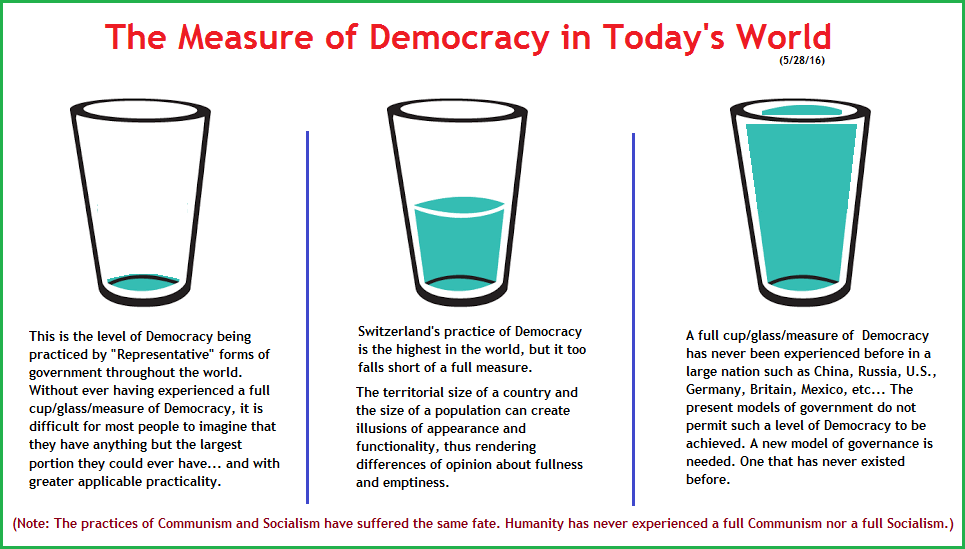

A Cenocratic Democracy is the Democracy for a New Government that many people are experiencing as a realization long overdue. For some it comes in the form of a personalized revelation that the government, and hence the nation, is on the wrong track. A new formula of governance is needed in order to adequately accommodate a dramatically increased level of democracy above and beyond that which is now being practiced. Indeed, the present model is the practice of a minuscule amount of democracy, even though a general query of the public might reveal they consider some alternative assessment. To illustrate the differences of how much democracy is being practiced and how far we have to go in order to get a full bowl/cup/glass/ ...measure of a public serviceable democracy, a glass filled with liquid, attached with explanations, will suffice for the present... until a movie is produced that will easily supplant the sincere, but otherwise incomplete ideas being provided in the Zeitgeist, Venus Project, and Runaway Slave productions— because the comments by numerous critics of these films, details considerations that are not being addressed for truly moving forward instead of sideways:

This philosophy is directed towards a massive expansion of government. Yes, that's right. We say there is the dire need for a Massive Expansion of Government. Promoting the need for a limited or smaller government is based on an unfinished logical deduction of democracy in its role as a formula of governance. Those calling for a limited government are asked to re-examine the foundation upon which their calculations are made, by becoming aware of a new algorithm. To wit:

When a "Democracy", a Peoples Government... is predicated on the established notion that it is a government OF, BY, and FOR ALL The People, this means the entire nation of a given population makes up, or at least should make up, the size of THEIR government. This is despite those arguments which insist that democracy is, and can only be defined in limited terms such as by Proportioned Representation... only because they are refusing to look outside the box they have pigeon-holed themselves in... and accept no other definition of democracy applicable to the human condition which can improve upon the few drops of democracy being rationed and raffled off to the people in various pecuniary outlines. If we take the size of a nation such as the United States, though any number of other nations can be used in respective equations; A Population of 300+ Million is a HUGE GOVERNMENT.

Hence, by its very nature, a Democracy is a BIG government.

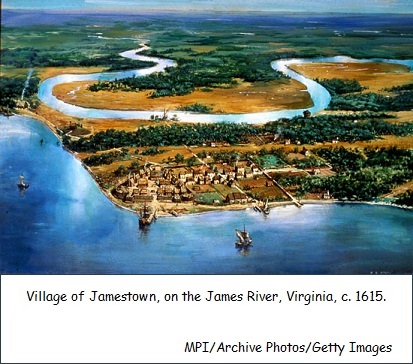

With respect to present day formulas of Representative Communism, Democracy and Socialism having been used, and specifically for the purposes at hand with respect to a U.S. applied distinction of reference; it is of need to briefly mention that it was the Virginia Company of the Jamestown Colony (summer of 1619) which introduced Representative Democracy... thereby initiating the establishment of the illusion of self-goverance placed into the hands of a select few... though the circumstances at the time no doubt inclined the people to think otherwise, since the concept at the time might have appeared quite novel and generous... given the dictatorial manner in which a monarchial-headed parlimentary system surely practiced its governance. Although there were other forms of "Representative" goverments having been practiced in history (Monarchy, Ecclesiastical, Ministerial, Senatorial, etc.), the Virginia Company of the newly founded colonial habitation appears to be the first instance of a Corporation (in a transitionally developing America) having influenced the structure of a democratically flavored government... so as to further its own aims in insecure colonial conditions where the need for total participation from the populace was at a premium... It was the establishment of a precedent followed by many of today's Corporate leaderships, due to their attempts to influence ideas resulting in a limited participation (and thus limited partnership) of/with the people by fostering the notion of limited government... thus furthering their aims by being able to influence the role of the people to persist in their modernized forms of indentured servitude... (as a workforce with little say-so in governance, truncated/obstructed/obfuscated socio-economic mobility, and high costs for basic living staples in today's world such as for shelter, clothing, training/education, transportation, child care, medical treatent, hygiene, food, etc.).

Representative democracy and slavery (1619)

In the summer of 1619 two significant changes occurred in the colony that would have lasting influence. One was the company's introduction of representative government to English America, which began on July 30 with the opening of the General Assembly. Voters in each of the colony's four cities, or boroughs, elected two burgesses to represent them, as did residents of each of the seven plantations. There were limitations to the democratic aspects of the General Assembly, however. In addition to the 22 elected burgesses, the General Assembly included six men chosen by the company. Consistent with the British practice of the time, the right to vote was most likely available only to male property owners. The colony's governor had power to veto the assembly's enactments, as did the company itself in London. Nonetheless, the body served as a precedent for self-governance in later British colonies in North America. The second far-reaching development was the arrival in the colony (in August) of the first Africans in English America. They had been carried on a Portuguese slave ship sailing from Angola to Veracruz, Mexico. While the Portuguese ship was sailing through the West Indies, it was attacked by a Dutch man-of-war and an English ship out of Jamestown. The two attacking ships captured about 50 slaves—men, women, and children—and brought them to outposts of Jamestown. More than 20 of the African captives were purchased there. Records concerning the lives and status of these first African Americans are very limited. It can be assumed that they were put to work on the tobacco harvest, an arduous undertaking. English law at this time did not recognize hereditary slavery, and it is possible that they were treated at first as indentured servants (obligated to serve for a specified period of time) rather than as slaves. Clear evidence of slavery in English America does not appear until the 1640s. Dissolution of the Virginia Company (1622–24) Chief Powhatan's successor, Opechancanough, carried out a surprise attack on the colony on the morning of March 22, 1622. The attack was strongest at the plantations and other English outposts that now lined the James River. The main settlement at Jamestown received a warning of the attack at the last minute and was able to mount a defense. Some 347 to 400 colonists died; reports of the death toll vary. The deaths that day represented between one-fourth and one-third of the colony's population of 1,240. The outcry in London over the attack, combined with political disagreements between James I and the company's leaders, led the king to appoint a commission in April 1623 to investigate the company's condition. Predictably, the commission returned a negative report. The king's advisers, the Privy Council, urged the company to accept a new charter that gave the king greater control over its operations. The company refused. On May 24, 1624, motivated in part by domestic political differences with the company's leadership, the king dissolved the company outright and made Virginia a royal colony, an arm of his government. Jamestown remained the colonial capital until Williamsburg became the capital in 1699. Source: "Jamestown Colony." Encyclopædia Britannica Ultimate Reference Suite, 2013. |

However, the formula of democracy being practiced through a "Representative" model, enforces an extremely limited practice of an existing Democratic reality that is obtainable by using a different social structure calculus. While various reasons are put forth for using the present architectural draft penciled in (quilled in) by the U.S. government's fore Fathers; the main reason for the present discussion has to do with being able to prevent a majority from exercising a lynch mob mentality on the rights of minorities. It is thought that the best way to offer protection against such an occurrence, is by way of Representation attached with the corollary of proportionism. (Even though examples from history may be shown to argue against this, such as the founding Fathers of America excluding so many from having equal rights, or Blacks needing the 13th, 14th, 15th Amendments and additional Civil Rights actions to accomplish some semblance of equanimity; though many Blacks still argue that they are not Free... and are only being subjected to another type of government-sponsored indentured servitude.)

The practice of a Limited Government is the practice of servitude, where property rights are little more than government lease programs... so long as you pay taxes. There is no actual property ownership. Ownership is based on one's ability to continue paying taxes. If you are an elderly person who lives a long life, you will eventually pay more in taxes than you did on purchasing your home.

The present amount (quality and quantity) of Democracy is being advertised and sold as a precious rarity in order to increase its value... sustained by the illusion that those who practice a Democracy are endowed with the highest level of Freedom, of Liberty, and of Justice that exists. In short, it's a bold-faced lie. Because all of us have been born into a limited practice of democracy, like a person having been born into slavery, we do not readily know what a full expression of Democracy is like... just as a person born into slavery has difficulty comprehending what a full measure of freedom would be like; even though various analogies might be configured within their acquired mental capacity of deduction.

Yet, the privileges and entitlements of the wealthy, as opposed to the deprivations experienced by the poor, can act as a beginning portrait of what the practice of a Cenocratic Democracy can provide us in contrast to the many differently experienced poverties that a Limited Democracy provide. Those seeking wealth know all too well there is both a quantitative and qualitative difference in the Liberty, Justice and Freedom provided by increased wealth. However, only a very few have contemplated what the wealth of an increased Democracy can profoundly initialize in all our lives.

Those who have referred to an increased practice in Democracy as an "Actual" or "Real" Democracy, are asked to use the label "Cenocratic Democracy", since it entails the proclamation for establishing a New Government. Yet, let us look at a short discussion concerning the idea of an "Actual Democracy" and associated complements, as excerpts taken from the Encyclopedia Britannica... with the added acknowledgment that the references include a recurring bias against the practice of such a Democracy... which act as humorous ancient inscriptions of taboo and warning against entering into a (traditionally observed) forbidden territory, based on manufactured superstitions embroidered by associations to impressions of authoritative disclosure and edict. It is necessary to make note of the age and place in which the commentators lived as a referential influence for establishing their idea. One should not be so quick to buy into their views which can be seen as rationalizations. Those skilled in argumentation based primarily on semantic derivations can convolute a discussion into a quagmired of dissolution so that no consensus is ever reached, until you press them for providing an alternative, at which time... their, or those whom they are Representing, may well show their self-centered motivation:

|

“Ideal democracy” As noted above (in the full article on Democracy), Aristotle found it useful to classify actually existing governments in terms of three “ideal constitutions.” For essentially the same reasons, the notion of an “ideal democracy” also can be useful for identifying and understanding the democratic characteristics of actually existing governments, be they of city-states, nation-states, or larger associations. It is important to note that the term ideal is ambiguous. In one sense, a system is ideal if it is considered apart from, or in the absence of, certain empirical conditions, which in actuality are always present to some degree. Ideal systems in this sense are used to identify what features of an actual system are essential to it, or what underlying laws are responsible, in combination with empirical factors, for a system's behaviour in actual circumstances. In another sense, a system is ideal if it is “best” from a moral point of view. An ideal system in this sense is a goal toward which a person or society ought to strive (even if it is not perfectly attainable in practice) and a standard against which the moral worth of what has been achieved, or of what exists, can be measured. These two senses are often confused. Systems that are ideal in the first sense may, but need not, be ideal in the second sense. Accordingly, a description of an ideal democracy, such as the one below, need not be intended to prescribe a particular political system. Indeed, influential conceptions of ideal democracy have been offered by democracy's enemies as well as by its friends. Features of ideal democracy At a minimum, an ideal democracy would have the following features:

Democracy, therefore, consists of more than just political processes; it is also necessarily a system of fundamental rights. Ideal and representative democracy In modern representative democracies, the features of ideal democracy, to the extent that they exist, are realized through a variety of political institutions. These institutions, which are broadly similar in different countries despite significant differences in constitutional structure, were entirely new in human history at the time of their first appearance in Europe and the United States in the 18th century. Among the most important of them is naturally the institution of representation itself, through which all major government decisions and policies are made by popularly elected officials, who are accountable to the electorate for their actions. Other important institutions include: Institutions like these developed in Europe and the United States in various political and historical circumstances, and the impulses that fostered them were not always themselves democratic. Yet, as they developed, it became increasingly apparent that they were necessary for achieving a satisfactory level of democracy in any political association as large as a nation-state. The relation between these institutions and the features of ideal democracy that are realized through them can be summarized as follows. In an association as large as a nation-state, representation is necessary for effective participation and for citizen control of the agenda; free, fair, and frequent elections are necessary for effective participation and for equality in voting; and freedom of expression, independent sources of information, and freedom of association are each necessary for effective participation, an informed electorate, and citizen control of the agenda. Actual democracies Since Aristotle's time (384 BCE - 322), political philosophers generally have insisted that no actual political system is likely to attain, to the fullest extent possible, all the features of its corresponding ideal. Thus, whereas the institutions of many actual systems are sufficient to attain a relatively high level of democracy, they are almost certainly not sufficient to achieve anything like perfect or ideal democracy. Nevertheless, such institutions may produce a satisfactory approximation of the ideal—as presumably they did in Athens in the 5th century BC, when the term democracy was coined, and in the United States in the early 19th century, when Tocqueville, like most others in America and elsewhere, unhesitatingly called the country a democracy. For associations that are small in population and area, the political institutions of direct democracy seem best to approximate the ideal of “government by the people.” In such a democracy all matters of importance to the association as a whole can be decided on by the citizens. Citizens have the opportunity to discuss the policies that come before them and to gather information directly from those they consider well-informed, as well as from other sources. They can meet at a convenient place—the Pnyx in Athens, the Forum in Rome, the Palazzo Ducale in Venice, or the town hall in a New England village—to discuss the policy further and to offer amendments or revisions. Finally, their decision is rendered in a vote, all votes being counted equal, with the votes of a majority prevailing. It is thus easy to see why direct democracies are sometimes thought to approach ideal democracy much more closely than representative systems ever could, and why the most ardent advocates of direct democracy have sometimes insisted, as Rousseau did in The Social Contract, that the term representative democracy is self-contradictory. Yet, views like these have failed to win many converts. Source: "Democracy." Encyclopædia Britannica Ultimate Reference Suite, 2013. |

Some readers will readily ascertain the the inclusion of some note of bias against an Actual Democracy being promoted or accepted, perhaps because the commentators were looking at the practice to be applied in their framework of government familiar to them. They were not looking at it with the idea of altering the overall formula of governance. Their governments used some model of Representation aligned with proportionism, be it a Monarchy, Parliament or the U.S. model of proportioned Representation.

As with many intellectual pursuits prior to actual experimentation, hypothesis are rendered along with the accompaniment of a thought experiment. Let three examples of thought processing be provided from the previous Britannica article already cited:

Dewey (Oct. 20, 1859 - June 1, 1952) According to the American philosopher John Dewey, democracy is the most desirable form of government because it alone provides the kinds of freedom necessary for individual self-development and growth—including the freedom to exchange ideas and opinions with others, the freedom to form associations with others to pursue common goals, and the freedom to determine and pursue one's own conception of the good life. Democracy is more than merely a form of government, however; as Dewey remarks in Democracy and Education (1916), it is also a “mode of associated life” in which citizens cooperate with each other to solve their common problems through rational means (i.e., through critical inquiry and experiment) in a spirit of mutual respect and good will. Moreover, the political institutions of any democracy, according to Dewey, should not be viewed as the perfect and unchangeable creations of visionary statesmen of the past; rather, they should be constantly subject to criticism and improvement as historical circumstances and the public interest change. Participation in a democracy as Dewey conceived it requires critical and inquisitive habits of mind, an inclination toward cooperation with others, and a feeling of public spiritedness and a desire to achieve the common good. Because these habits and inclinations must be inculcated from a young age, Dewey placed great emphasis on education; indeed, he called public schools “the church of democracy.” His contributions to both the theory and practice of education were enormously influential in the United States in the 20th century (see also education, philosophy of). Dewey offered little in the way of concrete proposals regarding the form that democratic institutions should take. Nevertheless, in The Public and Its Problems (1927) and other works, he contended that individuals cannot develop to their fullest potential except in a social democracy, or a democratic welfare-state. Accordingly, he held that democracies should possess strong regulatory powers. He also insisted that among the most important features of a social democracy should be the right of workers to participate directly in the control of the firms in which they are employed. Given Dewey's interest in education, it is not surprising that he was greatly concerned with the question of how citizens might better understand public affairs. Although he was a proponent of the application of the social sciences to the development of public policy, he sharply criticized intellectuals, academics, and political leaders who viewed the general public as incompetent and who often argued for some form of democratic elitism. Only the public, he maintained, can decide what the public interest is. In order for citizens to be able to make informed and responsible decisions about their common problems, he thought, it is important for them to engage in dialogue with each other in their local communities. Dewey's emphasis on dialogue as a critical practice in a democracy inspired later political theorists to explore the vital role of deliberation in democratic systems. Habermas (June 18, 1929 -) In a series of works published after 1970, the German philosopher and social theorist Jürgen Habermas, employing concepts borrowed from Anglo-American philosophy of language, argued that the idea of achieving a “rational consensus” within a group on questions of either fact or value presupposes the existence of what he called an “ideal speech situation.” In such a situation, participants would be able to evaluate each other's assertions solely on the basis of reason and evidence in an atmosphere completely free of any nonrational “coercive” influences, including both physical and psychological coercion. Furthermore, all participants would be motivated solely by the desire to obtain a rational consensus, and no time limits on the discussion would be imposed. Although difficult if not impossible to realize in practice, the ideal speech situation can be used as a model of free and open public discussion and a standard against which to evaluate the practices and institutions through which large political questions and issues of public policy are decided in actual democracies. Rawls (Feb. 21, 1921 - Nov. 24, 2002) From the time of Mill until about the mid-20th century, most philosophers who defended democratic principles did so largely on the basis of utilitarian considerations—i.e., they argued that systems of government that are democratic in character are more likely than other systems to produce a greater amount of happiness (or well-being) for a greater number of people. Such justifications, however, were traditionally vulnerable to the objection that they could be used to support intuitively less-desirable forms of government in which the greater happiness of the majority is achieved by unfairly neglecting the rights and interests of a minority. In A Theory of Justice (1971), the American philosopher John Rawls attempted to develop a nonutilitarian justification of a democratic political order characterized by fairness, equality, and individual rights. Reviving the notion of a social contract, which had been dormant since the 18th century, he imagined a hypothetical situation in which a group of rational individuals are rendered ignorant of all social and economic facts about themselves—including facts about their race, sex, religion, education, intelligence, talents or skills, and even their conception of the “good life”—and then asked to decide what general principles should govern the political institutions under which they live. From behind this “veil of ignorance,” Rawls argues, such a group would unanimously reject utilitarian principles—such as “political institutions should aim to maximize the happiness of the greatest number”—because no member of the group could know whether he belonged to a minority whose rights and interests might be neglected under institutions justified on utilitarian grounds. Instead, reason and self-interest would lead the group to adopt principles such as the following:

(Rawls holds that, given certain assumptions about human motivation, some inequality in the distribution of wealth may be necessary to achieve higher levels of productivity. It is therefore possible to imagine unequal distributions of wealth in which those who are least well-off are better off than they would be under an equal distribution.) These principles amount to an egalitarian form of democratic liberalism. Rawls is accordingly regarded as the leading philosophical defender of the modern democratic capitalist welfare state. Source: "Democracy." Encyclopædia Britannica Ultimate Reference Suite, 2013. |

Yet, not only is there a need for restructuring the government in order for the people to experience a "Full Serving" of democracy, but education systems would also be required to deliver a better grasp of the intent and functionality of such a system. Nonetheless, in playing the Devil's advocate, let us look at some comments from the same Britannica "Democracy" article that considers the question of Democracy's value:

The value of democracy Why should “the people” rule? Is democracy really superior to any other form of government? Although a full exploration of this issue is beyond the scope of this article (see political philosophy), history—particularly 20th-century history— demonstrates that democracy uniquely possesses a number of features that most people, whatever their basic political beliefs, would consider desirable:

Other features of democracy also would be considered desirable by most people, though some would regard them as less important than (1) through (4) above:

Finally, there are some features of democracy that some people—the critics of democracy—would not consider desirable at all, though most people, upon reflection, would regard them as at least worthwhile:

These advantages notwithstanding, there have been critics of democracy since ancient times. Perhaps the most enduring of their charges is that most people are incapable of participating in government in a meaningful or competent way because they lack the necessary knowledge, intelligence, wisdom, experience, or character. According to Plato, for example, the best government would be an aristocracy of “philosopher-kings” whose rigorous intellectual and moral training would make them uniquely qualified to rule. The view that the people as a whole are incapable of governing themselves has been espoused not only by kings and aristocratic rulers but also by political theorists (Plato foremost among them), religious leaders, and other authorities. The view was prevalent in one form or another throughout the world during most of recorded history until the early 20th century, and since then it has been most often invoked by opponents of democracy in Europe and elsewhere to justify various forms of dictatorship and one-party rule. No doubt there will be critics of democracy for as long as democratic governments exist. The extent of their success in winning adherents and promoting the creation of nondemocratic regimes will depend on how well democratic governments meet the new challenges and crises that are all but certain to occur. Source: "Democracy." Encyclopædia Britannica Ultimate Reference Suite, 2013. |

The present practices of limited democracy are unknowingly being disguised by many who clamor for some sort of "Limited Government" regime, when in fact the people are already subjected to such disparaging nonsense. Such practices are realistically unable to meet the new challenges and crises of our times. Those whose efforts are sincere in attempting to create better social conditions are unwaringly trying to apply fixes within the structure of a governing process that is anti-thetical to accomplishing the task... thus making such promoters devise rationalizations for magnifying the results of the small accomplishments which appear to unfold. Such people need to think outside the conventional paradigms of their sociological perspective and see them for what they are: Crude instruments coveted by embraced sentimentality and traditions based on an incomplete picture of democracy.

Those of us interested in making astute changes for improving the lives of all peoples in society must collaborate, concentrate and communicate comprehensively. We must coordinate a unified effort to ask for more government as defined by a full full bowl/cup/glass/...measure of serviceable democracy. We owe it to ourselves and the future of humanity to look beyond the veil of present ignorances... like an early primate peering through jungle foliage onto a Savannah clearing, and deciding to venture forth, though others may be shouting alarms bred from long- established fears gilded by various superstitions presumed from their perspective to be the foremost knowledge and wisdom... yet binds them and us, to perpetuating that which we know is less than that which may be accomplished as an expression of a life yet to be explored for a greater fulfillment of our human capacity for growth. Hence, Let us ask for more democracy guided by the auspices of a New Government... a Cenocracy, in order to remove ourselves from the recurring tyranny of a governing style that practices varying representations of basic needs deprivations... which perpetuate a pathetic and pitiful program of impoverished social slavery that is not appreciated— because we have all been born into a situation that not only presents us with delusions of grandeur, but also teaches a singular world view of illusory content as if it were the only and best possible reality. The blinders must be removed. The shackles must fall away. So that we may take the first step towards a greater realization of Justice, Freedom, and Liberty.

Date of Page Origination: Saturday, 28-May-2016... 03:21 AM

Initial Posting: Thursday, 28-May-2016... 10:54 AM

Updated Posting: Tuesday, 19-Jul-2016... 11:51 AM